It was a pleasant Saturday morning in Pune. I had to attend a family reunion at my relative’s place for which I was already late. While I was in the bath, the music on my phone was replaced with my ringtone. With wet hands, I reached out to see the caller ID. It was my team lead, which meant bad news was to be followed.

You see, we had planned to migrate our production cluster from kops to EKS that day. It was the first weekend after New Year’s, we chose this time window due to it being the least traffic period for our platform. I had just come back from a week-long beach trip and was still in vacation mindset; not at all ready, nor aware of what I was about to face.

Me: “Hello Vivek”

Vivek: “We have a situation, the platform is behaving really slowly, do you know what it could be ?"

I knew that something would go wrong but never expected it to be a networking problem. After all, one of the major reasons for moving to EKS was a better networking experience, weave was proving very problematic to us.

Me: “I don’t know what it could be, are you seeing any pattern?"

Vivek: “It’s too early to tell, but we will be reverting soon, it’s too unstable to carry on."

“Shit” were the only words out of my mouth. We had been planning this for a long time. Right before going on vacation, I had setup a new production cluster and deployed all the required tooling on it. My colleague Sumit had migrated all the production apps on it while I was away.

I was pretty sure I didn’t make any mistake while setting up the cluster, and Sumit has very stable hands when it comes to production. What could it be?

We raised a case with AWS Support citing an issue with EKS, thinking they might have an answer. After reading our case details, they transferred it to a networking expert.

Pump and dump

Let’s call the networking expert Matthew.

Matthew had asked us to do a packet capture so that he could dig deeper into the problem. After doing that, we finally saw a pattern.

All the internal network calls inside the cluster were working fine. But calls outside our cluster were failing. We run a few microservices on EC2 machines behind an NLB (Network Load Balancer) and all of those calls were failing intermittently.

Going further down the rabbit hole, we basically did a packet capture on the pods sending out the requests, the Kubernetes nodes the pods were running on, and the EC2 machines that were receiving these calls.

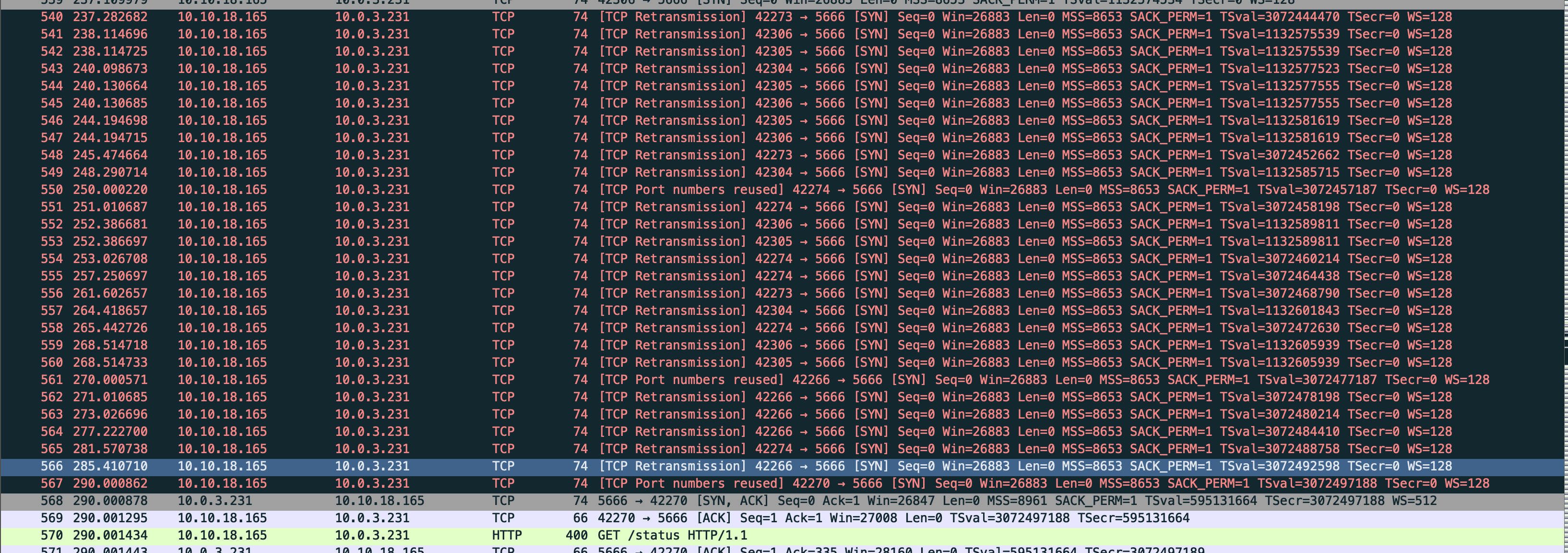

What we saw was a lot of packet re-transmissions between the Kubernetes node and the EC2 server.

My gut-feeling was shouting that it had to be something with the AWS’s CNI and their promise of providing each pod its own private IP. After all, this setup was working fine with our kops-based cluster.

For those who do not know, CNI (Container Networking Interface) is a specification used to configure network interfaces for linux containers. It is responsible for inserting a network interface into the container network namespace and making any necessary changes on the host.

Kubernetes provides its own specifications for CNI which are generally implemented by plugins using linux modules (iptables, netfilter, etc).

As per Matthew, the packet captures pointed towards an error in the server configuration. How could that be possible? These servers are working fine and serving the production workload. He then asked us to capture socket stats and network stats along with the tcpdumps. He was sure there was an error/misconfiguration on the EC2 machines and not any error on EKS.

We created artificial traffic to obtain more detailed packet captures, sent them to Matthew, he analysed them and asked us to capture a different set of data. Performing packet captures for debugging this became a part of my daily routine.

This traffic pumping and tcp-dumping went for a month, util I noticed an interesting anomaly.

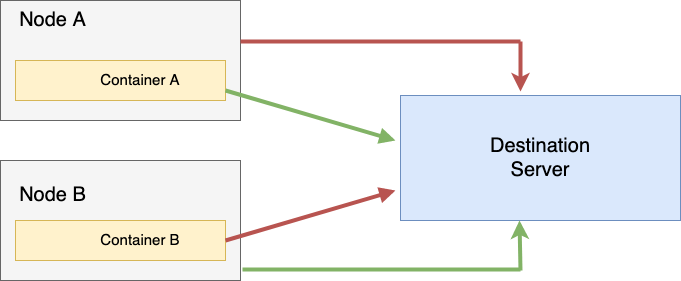

I had setup scripts to check the connections between the various entities involved, and I reached a state where if I hit the status endpoint from Pod-A running on Node-A I was able to reach it, but if I hit it directly from Node-A, I was not. And when I tried the same from Pod-B running on Node-B, I was able to reach the server from the Node-B but not from Pod-B.

This type of cross-wired functioning led me back to thinking it had to be EKS’s fault.

Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

– Arthur Conan Doyle

After all, the server should not care whether you are connecting from a container or a node, and even if it somehow does, the reverse should not have happened. We then scheduled a call with Matthew and asked him to loop in AWS’s Kubernetes experts as well.

A suggestion

The call was on a Thursday. It was a meeting room of 4 people with me, Sumit and Vivek listening in. After explaining the randomness, they asked us to make a few tweaks on the networking module on the node. Funnily enough, one thing led to another, and the networking stopped working on that node altogether. We were not able to reach the outside Internet. Since networking was down completely, we could also not install any tools to debug this further.

Since we were not facing many issues with ELB, we decided to use that for the time being. Just before ending the call with the Amazon team, they suggested something that would prove to be the key to unravelling this whole mystery. A simple configuration toggle that would change the course of our lives. He asked us to try using AWS_VPC_K8S_CNI_EXTERNALSNAT=true setting.

We tried it, and to everyone’s surprise, things magically started working as they should have from the beginning. This meant only one thing, time to take a deeper look into the CNI.

How it works

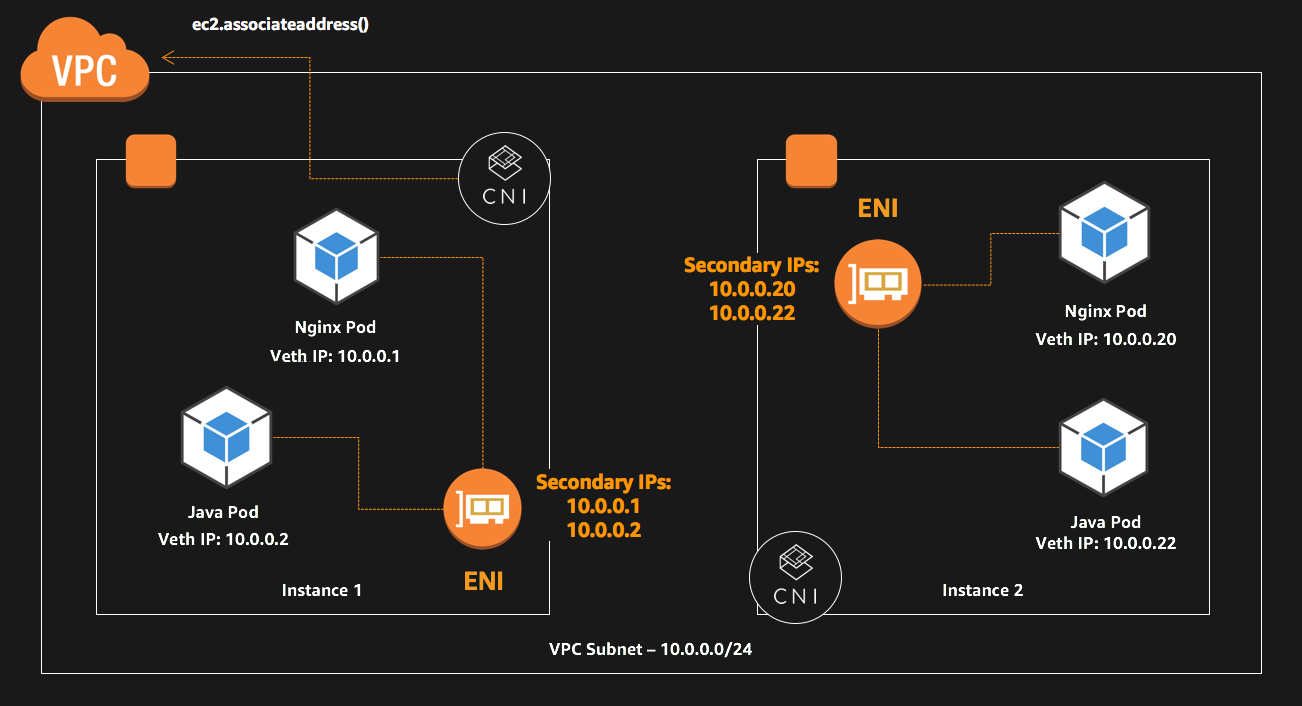

The role of the AWS CNI plugin is to allocate VPC IP addresses to Kubernetes nodes and configure the necessary networking for pods on each node. The folks at Amazon decided to take one step further and be a bit brave. The AWS CNI also creates secondary IP addresses at the instance level, thus assigning each pod their own IP and making it accessible directly from outside the cluster.

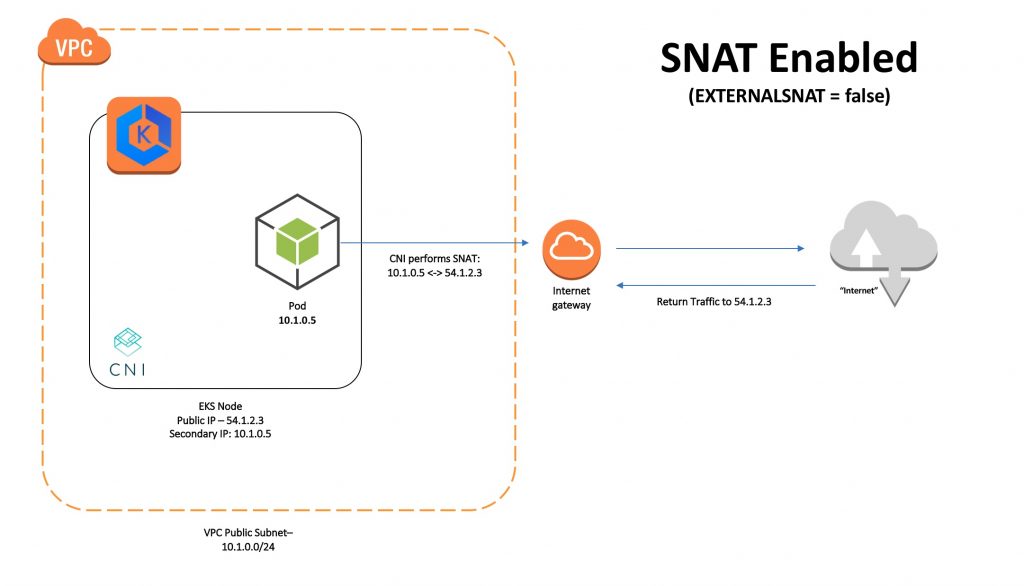

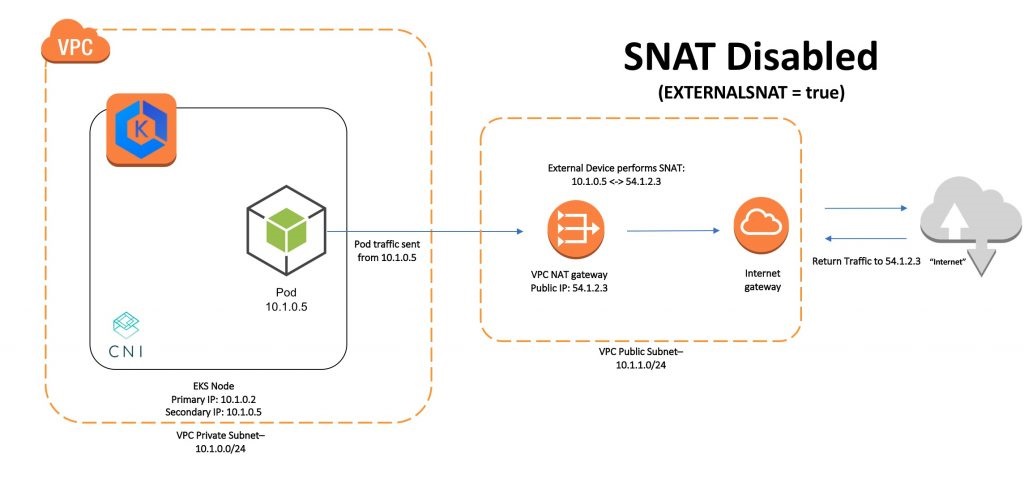

So, what role does AWS_VPC_K8S_CNI_EXTERNALSNAT=true play ?

Communication within a VPC (such as pod to pod) is direct between private IP addresses and requires no source network address translation (SNAT). When traffic is destined for an address outside of the VPC, the Amazon VPC CNI plugin for Kubernetes translates the private IP address of each pod to the primary private IP address assigned to the primary elastic network interface (network interface) of the node that the pod is running on.

Since the NLBs were in a different VPC, SNAT was taking place at the node via the CNI plugin. In this scenario, the CNI plugin was translating the IP address of the pod to the IP address of the internet gateway, but, in the absence of an internet gateway, everything falls apart.

Once external SNAT is enabled, the CNI plugin does not do any address translation. Traffic from the pod to the internet is translated by the NAT gateway.

Aftermath

Since moving to External SNAT, the cluster has not faced any networking problems till now, and I am happy to say that all our traffic is now migrated on to EKS without many hiccups.

We also setup monitoring and alerting on the AWS CNI as well to prevent any unforeseen complication from catching us off-guard.

Learnings

There was a lot to take away from this month and a half long ordeal.

- While debugging any issue, especially in networking, all components across the stack should be suspects. Ruling out EKS as a possible culprit led to us wasting a lot of valuable time.

- Add observability tools to your workflow. It was only after we saw bizarre connection anomalies (using our pinger daemon-set where every component was being pinged by another), we were able to move closer towards our solution.

- Know thy system. Before the migration, we just browsed through the AWS CNI’s documentation instead of thoroughly going through it’s implementation. Had we known its internal working, we could have made better judgements in our debugging technique and hypothesised better about what was happening behind the scenes.

Follow the discussion at Hacker News

Further Reading

- AWS Blog for handling external SNAT (CNI architecture diagrams were taken from here)

- A reason for unexplained connection timeouts on Kubernetes/Docker

- Github discussion on external SNAT in AWS CNI